ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial.

Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)

[published correction appears in JAMA 2003 Jan 8;289(2):178] [published correction appears in JAMA. 2004 May 12;291(18):2196]. JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981‐2997. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.2981

論文→Shaperで原文を整える→DeepLに翻訳させる

この作業だけをして、翻訳を載せています。そのため、ニュアンスがおかしい翻訳になることがあります(体感的にはDeepL翻訳の精度は高いのでチンプンカンプンな文章になることは少ないと思っています)。

Context

降圧療法は高血圧関連の罹患率や死亡率を下げるために確立されているが、最適な第一段階の治療法は知られていない。

目的

カルシウムチャネル遮断薬またはアンジオテンシン変換酵素阻害薬による治療が、利尿薬による治療と比較して、冠動脈性心疾患(CHD)またはその他の心血管疾患(CVD)イベントの発生率を低下させるかどうかを判断する。

研究デザイン

1994年2月から2002年3月まで実施された無作為化二重盲検活性化対照臨床試験「心臓発作を予防する降圧・脂質低下治療試験(ALLHAT)」。

セッティングと参加者

北米の623のセンターから、55歳以上で高血圧と他の少なくとも1つのCHD危険因子を持つ合計33357人が参加した。

介入

参加者は、約4~8年の追跡調査を計画して、クロルタリドン12.5~25mg/d(n = 15 255)、アムロジピン2.5~10mg/d(n = 9048)、またはリシノプリル10~40mg/d(n = 9054)の投与を受けるように無作為に割り付けられた。

主要アウトカムと測定

主要転帰は致死的CHDまたは非致死的心筋梗塞の複合であり、intent-to-treatで解析された。副次的転帰は、全死因死亡、脳卒中、複合CHD(主要転帰、冠動脈血行再建術、または入院を伴う狭心症)、複合CVD(複合CHD、脳卒中、入院なしで治療した狭心症、心不全[HF]、末梢動脈疾患)であった。

結果

平均追跡期間は4.9年であった。

主要アウトカムは2956人の参加者で発生し、治療法間の差はなかった。クロルタリドン(6年率11.5%)と比較して、相対リスク(RR)はアムロジピン(6年率11.3%)で0.98(95%CI、0.90-1.07)、リシノプリル(6年率11.4%)で0.99(95%CI、0.91-1.08)であった。

同様に、全死因死亡率は群間で差がなかった。5年収縮期血圧は、アムロジピン(0.8mmHg、P=.03)群とリシノプリル(2mmHg、P<.001)群でクロルタリドンと比較して有意に高く、5年拡張期血圧はアムロジピン(0.8mmHg、P<.001)群で有意に低かった。

アムロジピンとクロルタリドンの副次的転帰は、アムロジピン群で6年間のHF発生率が高かった(10.2%対7.7%;RR、1.38;95%CI、1.25-1.52)以外は同様であった。リシノプリルとクロルタリドンでは、リシノプリルの方が複合CVD(33.3%対30.9%;RR、1.10;95%CI、1.05-1.16)、脳卒中(6.3%対5.6%;RR、1.15;95%CI、1.02-1.30)、HF(8.7%対7.7%;RR、1.19;95%CI、1.07-1.31)の6年率が高かった。

結論

チアジド系利尿薬は、1種類以上の主要なCVDの予防に優れており、価格も安価である。最初の段階の降圧療法には、これらの薬剤を優先すべきである。

References

- American Heart Association. 2002 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. Dallas, Tex: American Heart Association; 2001.

- Cutler JA, MacMahon SW, Furberg CD. Controlled clinical trials of drug treatment for hypertension: a review. Hypertension.1989;13:I36-I44.Google Scholar

- Psaty BM, Smith NL, Siscovick DS. et al. Health outcomes associated with antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA.1997;277:739-745.Google Scholar

- The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med.1997;157:2413-2446.Google Scholar

- Chalmers J, Zanchetti A. The 1996 report of a World Health Organization expert committee on hypertension control. J Hypertens.1996;14:929-933.Google Scholar

- Collins R, Peto R, Godwin J, MacMahon S. Blood pressure and coronary heart disease. Lancet.1990;336:370-371.Google Scholar

- World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Protocol for prospective collaborative overviews of major randomized trials of blood pressure lowering treatments. J Hypertens.1998;16:127-137.Google Scholar

- SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA.1991;265:3255-3264.Google Scholar

- Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L. et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension: the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet.1997;350:757-764.Google Scholar

- Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J. et al. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients: the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med.2000;342:145-153.Google Scholar

- PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet.2001;358:1033-1041.Google Scholar

- Grimm Jr RH. Antihypertensive therapy: taking lipids into consideration. Am Heart J.1991;122:910-918.Google Scholar

- Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman N. Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood-pressure-lowering drugs: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials: Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Lancet.2000;356:1955-1964.Google Scholar

- Pahor M, Psaty BM, Alderman MH. et al. Health outcomes associated with calcium antagonists compared with other first-line antihypertensive therapies: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet.2000;356:1949-1954.Google Scholar

- Poulter NR. Treatment of hypertension: a clinical epidemiologist’s view. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol.1991;18(suppl 2):S35-S38.Google Scholar

- Neaton JD, Grimm Jr RH, Prineas RJ. et al. Treatment of mild hypertension study: final results: Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study Research Group. JAMA.1993;270:713-724.Google Scholar

- Materson BJ, Reda DJ, Cushman WC. et al. Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men: a comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo: the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. N Engl J Med.1993;328:914-921.Google Scholar

- Davis BR, Cutler JA, Gordon DJ. et al. Rationale and design for the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). Am J Hypertens.1996;9:342-360.Google Scholar

- The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized to doxazosin vs chlorthalidone: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA.2000;283:1967-1975.Google Scholar

- Davis BR, Cutler JA, Furberg CD. et al. Relationship of antihypertensive treatment regimens and change in blood pressure to risk for heart failure in hypertensive patients randomly assigned to doxazosin or chlorthalidone: further analyses from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Ann Intern Med.2002;137:313-320.Google Scholar

- The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs usual care: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. JAMA.2002;288:2998-3007.Google Scholar

- Grimm Jr RH, Margolis KL, Papademetriou V. et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). Hypertension.2001;37:19-27.Google Scholar

- The fifth report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC V). Arch Intern Med.1993;153:154-183.Google Scholar

- Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB. et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med.1999;130:461-470.Google Scholar

- Levey AS, Greene T, Kusek JW. et al. A simplified equation to predict glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine. J Am Soc Nephrol.2000;11:155A.Google Scholar

- Piller LB, Davis BR, Cutler JA. et al. Validation of heart failure events in ALLHAT participants assigned to doxazosin. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med.2002;3:10.Google Scholar

- Public Health Service-Health Care Financing Administration. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). 6th ed. Bethesda, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2001. DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 80-1260.

- Dunnett CW. A multiple comparisons procedure for comparing several treatments with a control. J Am Stat Assoc.1955;50:1096-1121.Google Scholar

- Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Regression. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1997.

- Davis BR, Hardy RJ. Upper bounds for type I and II error rates in conditional power calculations. Commun Stat.1990;19:3571-3584.Google Scholar

- Lan KKG, DeMets DL. Discrete sequential boundaries for clinical trials. Biometrika.1983;70:659-663.Google Scholar

- Hansson L, Lindholm LH, Ekbom T. et al. Randomised trial of old and new antihypertensive drugs in elderly patients: cardiovascular mortality and morbidity: the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2 study. Lancet.1999;354:1751-1756.Google Scholar

- Brown MJ, Palmer CR, Castaigne A. et al. Morbidity and mortality in patients randomised to double-blind treatment with a long-acting calcium-channel blocker or diuretic in the International Nifedipine GITS study: Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT). Lancet.2000;356:366-372.Google Scholar

- MacMahon S, Neal B. Differences between blood-pressure-lowering drugs. Lancet.2000;356:352-353.Google Scholar

- Kostis JB, Davis BR, Cutler J. et al. Prevention of heart failure by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA.1997;278:212-216.Google Scholar

- Ad Hoc Subcommittee of the Liaison Committee of the World Health Organisation and the International Society of Hypertension. Effects of calcium antagonists on the risks of coronary heart disease, cancer and bleeding. J Hypertens.1997;15:105-115.Google Scholar

- Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Meyer JV. Nifedipine: dose-related increase in mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation.1995;92:1326-1331.Google Scholar

- Agodoa LY, Appel L, Bakris GL. et al. Effect of ramipril vs amlodipine on renal outcomes in hypertensive nephrosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA.2001;285:2719-2728.Google Scholar

- Hall WD, Kusek JW, Kirk KA. et al. Short-term effects of blood pressure control and antihypertensive drug regimen on glomerular filtration rate: the African-American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Pilot Study. Am J Kidney Dis.1997;29:720-728.Google Scholar

- ter Wee PM, De Micheli AG, Epstein M. Effects of calcium antagonists on renal hemodynamics and progression of nondiabetic chronic renal disease. Arch Intern Med.1994;154:1185-1202.Google Scholar

- Lonn EM, Yusuf S, Jha P. et al. Emerging role of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in cardiac and vascular protection. Circulation.1994;90:2056-2069.Google Scholar

- Weir MR, Dzau VJ. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: a specific target for hypertension management. Am J Hypertens.1999;12:205S-213S.Google Scholar

- Jafar TH, Schmid CH, Landa M. et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and progression of nondiabetic renal disease: a meta-analysis of patient-level data. Ann Intern Med.2001;135:73-87.Google Scholar

- Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions: the SOLVD Investigators. N Engl J Med.1992;327:685-691.Google Scholar

- Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S. et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease: Part 2, short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet.1990;335:827-838.Google Scholar

- MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J. et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease: Part 1, prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet.1990;335:765-774.Google Scholar

- Staessen JA, Byttebier G, Buntinx F. et al. Antihypertensive treatment based on conventional or ambulatory blood pressure measurement: a randomized controlled trial: Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring and Treatment of Hypertension Investigators. JAMA.1997;278:1065-1072.Google Scholar

- Franklin SS. Cardiovascular risks related to increased diastolic, systolic and pulse pressure: an epidemiologist’s point of view. Pathol Biol (Paris).1999;47:594-603.Google Scholar

- Saunders E, Weir MR, Kong BW. et al. A comparison of the efficacy and safety of a beta-blocker, a calcium channel blocker, and a converting enzyme inhibitor in hypertensive blacks. Arch Intern Med.1990;150:1707-1713.Google Scholar

- Rahman M, Douglas JG, Wright JT. Pathophysiology and treatment implications of hypertension in the African-American population. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am.1997;26:125-144.Google Scholar

- Cushman WC, Reda DJ, Perry HM. et al. Regional and racial differences in response to antihypertensive medication use in a randomized controlled trial of men with hypertension in the United States. Arch Intern Med.2000;160:825-831.Google Scholar

- Exner DV, Dries DL, Domanski MJ, Cohn JN. Lesser response to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor therapy in black as compared with white patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med.2001;344:1351-1357.Google Scholar

- Carson P, Ziesche S, Johnson G, Cohn JN. Racial differences in response to therapy for heart failure: analysis of the vasodilator-heart failure trials: Vasodilator-Heart Failure Trial Study Group. J Card Fail.1999;5:178-187.Google Scholar

- Dries DL, Strong MH, Cooper RS, Drazner MH. Efficacy of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in reducing progression from asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction to symptomatic heart failure in black and white patients. J Am Coll Cardiol.2002;40:311-317.Google Scholar

- Manolio TA, Cutler JA, Furberg CD. et al. Trends in pharmacologic management of hypertension in the United States. Arch Intern Med.1995;155:829-837.Google Scholar

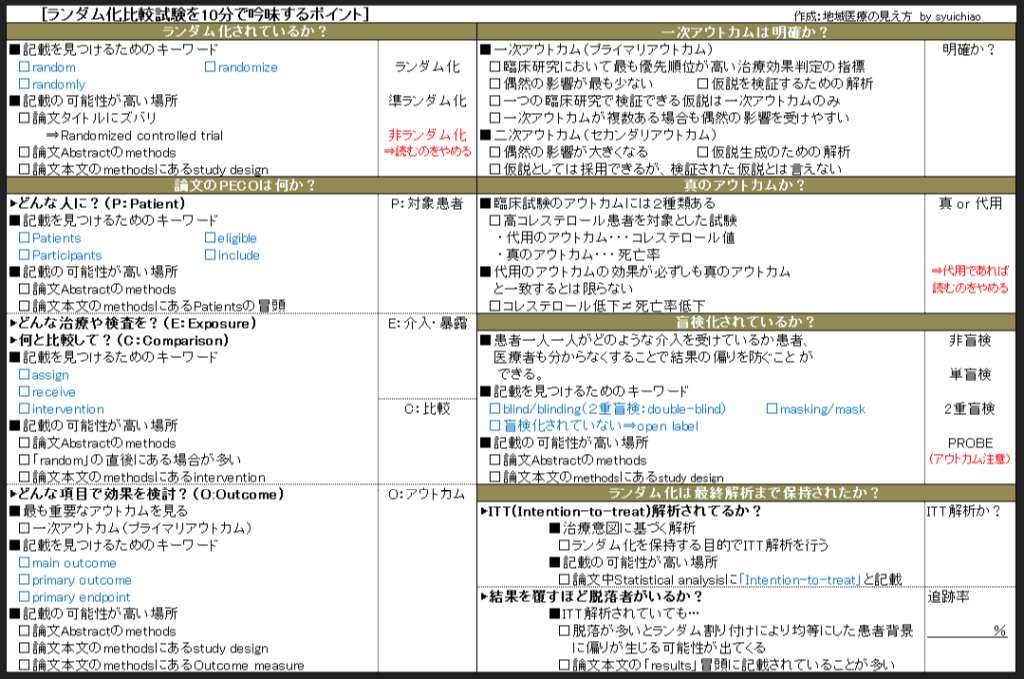

チェック項目(ランダム化比較試験)

ランダム化されてるか?

| ✅ | ランダム化されている |

| ☐ | ランダム化されていない |

論文のPECO

| P | ステージ1またはステージ2の高血圧症で、CHDイベントのリスク因子を1つ以上追加した55歳以上の男女33,357人(平均年齢66.9歳 , 女性47%) *入院歴または治療歴のある症候性心不全(HF)および/または左室駆出率が35%未満であることが知られている患者は除外 |

| E1 | アムロジピン2.5~10mg/d(n = 9048)を投与 |

| E2 | リシノプリル10~40mg/d(n = 9054)を投与 |

| C | クロルタリドン12.5~25mg/d(n = 15 255)を投与 |

| O | 致死的CHDまたは非致死的心筋梗塞の複合の発生率 |

1次アウトカムは明確か?

| ✅ | 明確である |

| ☐ | 明確ではない |

論文のアウトカムは真のアウトカムか?

| ✅ | 真のアウトカムである |

| ☐ | 代用のアウトカムである |

盲検化されているか?

| ▢ | 非盲検化 |

| ▢ | 単盲検化 |

| ✅ | 二重盲検化 |

| ▢ | PROBE法 |

追跡機関と解析方法は?

| 追跡期間(追跡率) | 4.9年(クロルタリドン群97.3%、アムロジピン群97.2%、リシノプリル群97%) |

| 解析方法 | ✅ ITT解析 ☐per protocol 解析 ▢FAS解析 |

研究結果

| P | ステージ1またはステージ2の高血圧症で、CHDイベントのリスク因子を1つ以上追加した55歳以上の男女33,357人(平均年齢66.9歳 , 女性47%) *入院歴または治療歴のある症候性心不全(HF)および/または左室駆出率が35%未満であることが知られている患者は除外 |

| E1 | アムロジピン2.5~10mg/d(n = 9048)を投与 |

| E2 | リシノプリル10~40mg/d(n = 9054)を投与 |

| C | クロルタリドン12.5~25mg/d(n = 15 255)を投与 |

| O | 致死的CHDまたは非致死的心筋梗塞の複合の発生率 |

| E1 | 798 / 9048 |

| E2 | 796 / 9054 |

| C | 1362 / 15255 |

| 相対危険度[95%CI] | E1/C = 0.98 ( 0.90-1.07 ) E2/C = 0.99 ( 0.91-1.08 ) |

感想

ランドマーク論文をちょくちょく読んでいこうと思っていて、先日のHYVETに引き続いて今回はALLHAT試験を読んでみました。

対象となっている患者さんの平均年齢が67歳と高齢者としては比較的若く、日々の業務で接することが多い年齢層なので興味深く読ませていただきました。

ACE阻害薬やCa拮抗薬は1stチョイスとして処方されることが多い印象ですが、チアジド系の利尿薬、論文の結果を読む限りですが非常に良さそうですね。とにかく値段が安いですし。

ちょうど今日読んだ他の論文と併せて読みしたので余計に「ええやん!」と思ってしまっている部分も多くありますが…。

最後にオススメ書籍の紹介